When large numbers of newcomers settle into a new land, it is predictable that those who have a settled before them will push back, fearing that their way of life will be forever changed. Even before the American Revolution, Benjamin Franklin worried that German immigrants would never assimilate into colonial society. One of the issues that concerned him most was language. Issues about language and immigration flared up again during World War I. The state of Iowa even temporarily banned foreign languages.

Language scholar Dennis Baron writes that schools were a central battleground in the war against foreign languages.

The schools opened up a second front in the Great War on foreign languages in World War I America. In 1918, the New York Times reported that as many as 25 states had already removed German from the curriculum, an action the newspaper applauded as “a matter of polity, of patriotism, of Americanism,” and “good hard common sense.”

Schools banned foreign languages from classrooms and schoolyards, promoting English not just as the best way to succeed in life, but also as the language for patriots. In 1918, the Chicago Woman’s Club launched Better American Speech Week to further this agenda. With slogans like “Speak the language of your flag”; “American Speech means American loyalty”; and “Better Speech for Better Americans,” children were encouraged to learn English, and those who already spoke the language were asked to speak it better.

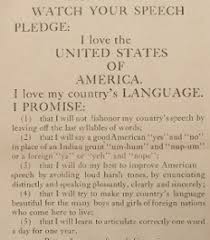

Schoolchildren had to take a “Watch Your Speech” pledge which began, “I love the United States of America. I love my country’s language,” and included among its promises, “that I will say a good American ‘yes’ and ‘no’ in place of an Indian grunt ‘un-hum’ and ‘nup-um’ or a foreign ‘ya’ or ‘yeh’ and ‘nope.’”

Better American Speech Week reflected the spirit of wartime America, encoding patriotism, the assimilation of immigrants, and a rejection of minority languages and dialects. It resonated with popular opinion and was embraced by schools and by the press from coast to coast. In addition to pledges and posters, schools recruited students to spy on the usage of their peers.

Baron explains that there were consequences for violating the new norms, including being forced to appear before student tribunals and facing public humiliation. Below is the Watch Your Speech Pledge that was promoted by the Chicago Woman’s Club.

The text reads:

I love the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.

I love my country’s LANGUAGE.

I PROMISE:

- That I will not dishonor my country’s speech by leaving off the last syllables of words;

- That I will say a good American “yes” and “no” in place of an Indian grunt “um-hum” and “nup-um” or a foreign “ya” or “yeah” and “nope.”

- That I will do my best to improve American speech by avoiding harsh tones, by encunciating distinctly, and speaking pleasantly, clearly, and distinctly;

- That I will try to make my country’s language beautiful for the many boys and girls of foreign nations who come here to live.

- That I will learn to articulate correctly one word a day for a year.

Reflection Questions

- What is the tone of the pledge? What words stand out to you as your read it?

- What was the goal of the pledge?

- Were efforts like Watch Your Speech and Better Speech Week positive? Were the negative? What impact do you think they had?

- Is there anything wrong with promoting standard speech and dialects? When, if ever, does promoting and teaching one language, lead to discrimination, prejudice, and stereotyping?