During World War I, anti-German attitudes in the U.S. impacted life all across the country. Immigrants from Germany had been coming to the United States since before the Declaration of Independence, in fact they were the largest immigrant group in the country for decades. For the most part, Germans had integrated, retaining elements of German culture while also finding ways to fit into the country and, for the most part, they had been accepted into American society. That changed when the United States went to war with Germany.

Language scholar Dennis Baron describes what happened next,

In April, 1917, the United States declared war on Germany. In addition to sending troops to fight in Europe, Americans waged war on the language of the enemy at home. German was the second most commonly-spoken language in America, and banning it seemed the way to stop German spies cold. Plus, immigrants had always been encouraged to switch from their mother tongue to English to signal their assimilation and their acceptance of American values. Now speaking English became a badge of patriotism as well, a way to prove that you were not a spy.

The war on language was fought on two fronts, one legal, the other, in the schools. Its impact was immediate and long-lasting. German was the target, but the other “foreign” tongues suffered collateral damage. Immigrant languages in America went into decline, and there was a precipitous drop in the study of foreign languages in US schools as well.

Boycotting German was the first step in the campaign, but legislating against the language quickly followed. Scribner’s was urged to publish no German titles during the war. Sheet music dealers refused to handle German songs. At least one American Berlin was renamed Liberty. Even German foods were rebranded. Just as later, during the Iraq War, French fries would become freedom fries, in the America of World War I, German fried potatoes became American fries, sauerkraut morphed into liberty cabbage, and superpatriots even caught the liberty measles.

On May 23, 1918, Iowa Governor went further when he made it illegal to speak a language other than English in public and on the telephone.

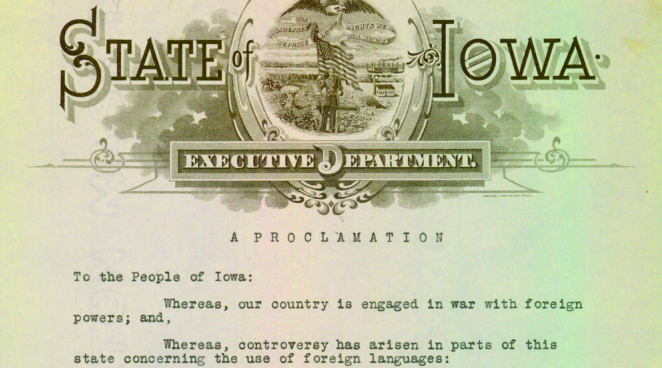

The text, of what is know as the Babel Proclamation is below:

To the People of Iowa:

Whereas, our country is engaged in war with foreign powers; and,

Whereas, controversy has arisen in parts of this state concerning the use of foreign languages: Therefore, for the purpose of ending such controversy and to bring about peace, quiet and harmony among our people, attention is directed to the following, and all are requested to govern themselves accordingly.

The official language of the United States and the state of Iowa is the English language. Freedom of speech is guaranteed by federal and state Constitutions, but this is not a guaranty of the right to use a language other than the language of this country — the English language. Both federal and state Constitutions also provide that “no laws shall be made respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” Each person is guaranteed freedom to worship God according to the dictates of his own conscience, but this guaranty does not protect him in the use of a foreign language when he can as well express his thought in English, nor entitle the person who cannot speak or understand the English language to employ a foreign language, when to do so tends, in time of national peril, to create discord among neighbors and citizens, or to disturb the peace and quiet of the community.

Every person should appreciate and observe his duty to refrain from all acts or conversation which may excite suspicion or produce strife among the people, but in his relation to the public should so demean himself that every word and act will manifest his loyalty to his country and his solemn purpose to aid in achieving victory for our army and navy and the permanent peace of the world.

If there must be disagreement, let adjustment be made by those in official authority rather than by the participants in the disagreement. Voluntary or self-constituted committees or associations undertaking the settlement of such disputes, instead of promoting peace and harmony, are a menace to society and a fruitful cause of violence. The great aim and object of all should be unity of purpose and a solidarity of all the people under the flag for victory. This much we owe to ourselves, to posterity, to our country and to the world.

Therefore, the following rules should obtain in Iowa during the war:

First. English should and must be the only medium of instruction in public, private, denominational or other similar schools.

Second. Conversation in public places, on trains and over the telephone should be in the English language.

Third. All public addresses should and must be in the English language.

Fourth. Let those who cannot speak or understand the English language conduct their religious worship in their homes.

This course carried out in the spirit of patriotism, though inconvenient to some, will not interfere with their guaranteed constitutional rights and will result in country in battle. The blessings of the United States are so great that any inconvenience or sacrifice should willingly be made for their perpetuity.

Therefore, by virtue of authority in me vested, I, W.L. Harding, Governor of the state of Iowa, commend the spirit of tolerance and urge that henceforward the within outlined rules be adhered to by all, that petty differences be avoided and forgotten, and that, united as one people with one purpose and one language, we fight shoulder to shoulder for the good of mankind.

In testimony whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and cause to be affixed the Great Seal of the State

of Iowa.Done at Des Moines, this twenty-third day of May, 1918.

By the Governor: W. L. Harding

W. S. Allen, Secretary of State.

The Babel Proclamation was revoked in December of the same year, but with an important exception, “the English language should be the only medium of instruction in all schools of state, weather public, private, denominational or otherwise, and no foreignlanguage should be taught in any school of grade lower than high school, and if taught it should be as a culture and not as a medium of instruction for other subjects.”

Revocation of Babel Proclamation, 1918 State of Iowa Executive Department

A Proclamation To the People of Iowa:

Whereas, on the 23d day of May, 1918, the undersigned, by virtue of authority in him vested as Governor of Iowa, issued a proclamation directing attention to the duty of all citizens during the progress of the war to “refrain from acts and conversations which might excite suspicion and strife among the people,” and requesting every person to “demean himself that every word and act would manifest his loyalty to his country and his solemn purpose to aid in achieving victory for our Army and Navy and the permanent peace of the world,” and declaring “ the great aim and object of all should be unity of purpose and solidarity of all the people under the flag for victory;” and

Whereas, to accomplish these purposes, it was proclaimed that certain rules should obtain, which were in substance that the English language should be employed as the medium of instruction in all schools, in conversation in public places and over telephones, and in public address, which, as was said, would “result in peace and tranquility at home and greatly strengthen the country in battle,” and suggesting that the blessings of our country were so great “ that any inconvenience or sacrifice should willingly be made for their perpetuity;” and

Whereas, the terms of the armistice joined in by all the belligerent powers include the resumption of war, the authority for issuing the rules laid down in the proclamation no longer continues as a war grant power; Now Therefore, in order to avoid any misunderstanding, notice is hereby given that said rules set out in the proclamation of May 23d, 1918, are no longer in force as an executive order. The people generally throughout the state are to be commended for patriotically conforming with the spirit and purpose of the Proclamation even though it involves some inconvenience or modification of custom.

The necessity for the solidarity of our people has been demonstrated to every American citizen during the war as never before. National Unity can be best maintained by the employment of a common vehicle of communication, and this vehicle in the United States, by reason of custom and law, is the English language. This does not mean that a citizen should be able to speak no other language. It does mean, however, That though he be conversant with another language or languages he should be able to make efficient use of the official language of the country and should use the same.

Further, the English language should be the only medium of instruction in all schools of state, weather public, private, denominational or otherwise, and no foreign language should be taught in any school of grade lower than high school, and if taught it should be as a culture and not as a medium of instruction for other subjects.

While we welcome enlightened and thrifty people to our shores and to all the advantages of free institutions under our representative form of government, this is not with the view, and should not be so interpreted, of enabling them to establish themselves in communities by themselves and thereby maintaining the language and customs of their former country. All should understand that they are welcome to come, but for the purpose of becoming a part of our own people, to learn and use our language, adopt our customs, and become citizens of our common country. In Testimony Whereof, I have here unto set my hand and caused to be affixed the Great Seal of the State of Iowa. Done at Des Moines, this fourth day of December, 1918. By the Governor: W. L. Harding W. S. Allen, Secretary of State.

Reflection Questions

- How do you explain the rise of anti-German sentiment during World War I? What do you think issues around language became so important?

- What arguments did Harding make to justify language restrictions?

- Compare the text of the revocation of the declaration to the declaration itself.

- What is similar?

- What is different?

- How do you explain the differences?

- Imagine you were a German immigrant in Iowa during this time. What would you want to tell the governor?

- These documents are over 100 years old. Consider their significance using the three whys thinking routine.