During the Great Depression, over 1 million people of Mexican ancestry were sent from the United States to Mexico. Over 60 percent of those relocated were U.S. citizens. While many people refer to these events as Mexican repatriation, how was it possible to repatriate people to Mexico who never lived there in the first place?

While some people did agree to go to Mexico, it is hard to say that these were voluntary decisions. Mexicans and Mexican Americans were facing increased hostility from law enforcement, politicians, and from many in the press.

Historian Francisco Balderrama, co-author Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s of explains:

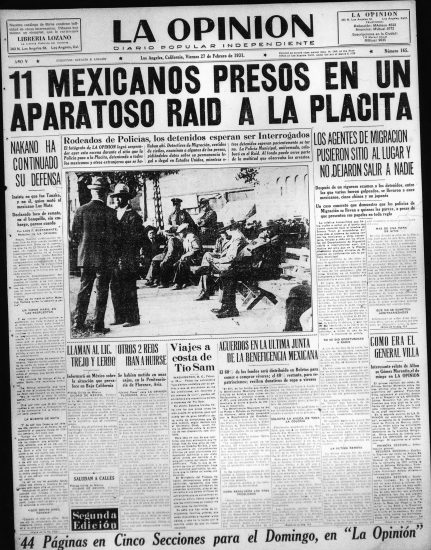

… During the Hoover administration in the late 1920s and early 1930s, particularly the winter of 1930-1931, William Dill (ph), the attorney general who had presidential ambitions, instituted a program of deportations. And it was announced that we need to provide jobs for Americans, and so we need to get rid of these other people. This created…tension in the Mexican community. And at the same time, U.S. Steel, Ford Motor Company, Southern Pacific Railroad said to their Mexican workers, you would be better off in Mexico with your own people. At the same time that that’s occurring, differing counties on the county level in some cases the state level, then decide to cut relief cost – their target at Mexican families.…[T]here was the development of a deportation desk from LA County relief agencies going out and recruiting Mexicans to go to Mexico…LA legal counsel says you can’t do that. That’s the responsibility, that’s the duty of the federal government. So they backed up and said, well, we’re not going to call it deportation. We’re going to call it repatriation. And repatriation carries connotations that it’s voluntary, that people are making their own decision without pressure to return to the country of their nationality. But most obviously, how voluntary is it if you have deportation raids by the federal government during the Hoover administration and people are disappearing on the streets? How voluntary is it if you have county agents knocking on people’s doors telling people oh, you would be better off in Mexico and here are your train tickets? You should be ready to go in two weeks. So……Sometimes families that did have individuals that were working maybe limited time, which was very common during the Great Depression, but scaring them and telling them well, I don’t know how long you’re going to keep that job. Maybe you better just go to Mexico because you’re liable to lose that particular job. And I think another factor is just waking up and looking at the newspaper, seeing that there’s raids. Here in Los Angeles, we had the very famous Placita raid, in which a part of Downtown Los Angeles is cornered off, and there’s banner headlines saying, deportation of Mexicans – not distinguishing between those with papers and not distinguishing those that are American citizens but always just referring to Mexicans and deportation of Mexicans and not making any of those distinctions. Those are the pressures that this population lived with…

Immigration historian Erica Lee believes that we need to use more accurate language to describe what happened. She explains,

“Because these efforts did not distinguish between longtime residents, undocumented immigrants, and American citizens of Mexican descent, this was not just a xenophobic campaign to get rid of foreigners–it was a race-based expulsion of Mexicans.” (Lee, America for Americans)

As the depression set in, politicians and civic leaders argued that Mexicans were taking jobs from deserving citizens. Of course, the argument ignores the fact that many of those targeted for deportation were citizens, citizens of Mexican descent. The producers of PBS’s Latino Americans explain that “Mexicans and Mexican-Americans were used as scapegoats during the depression, and forced to leave on trains. Many of them were not allowed back into the country.”

This clip from PBS’s Latino Americans provides explores anti-Mexican xenophobia during the depression of the 1930s.

Educators at the Boulder Latino History Project curated a set of primary and secondary source documents to teach the impact of the expulsion of Mexicans and Mexican Americans in Boulder, Colorado.

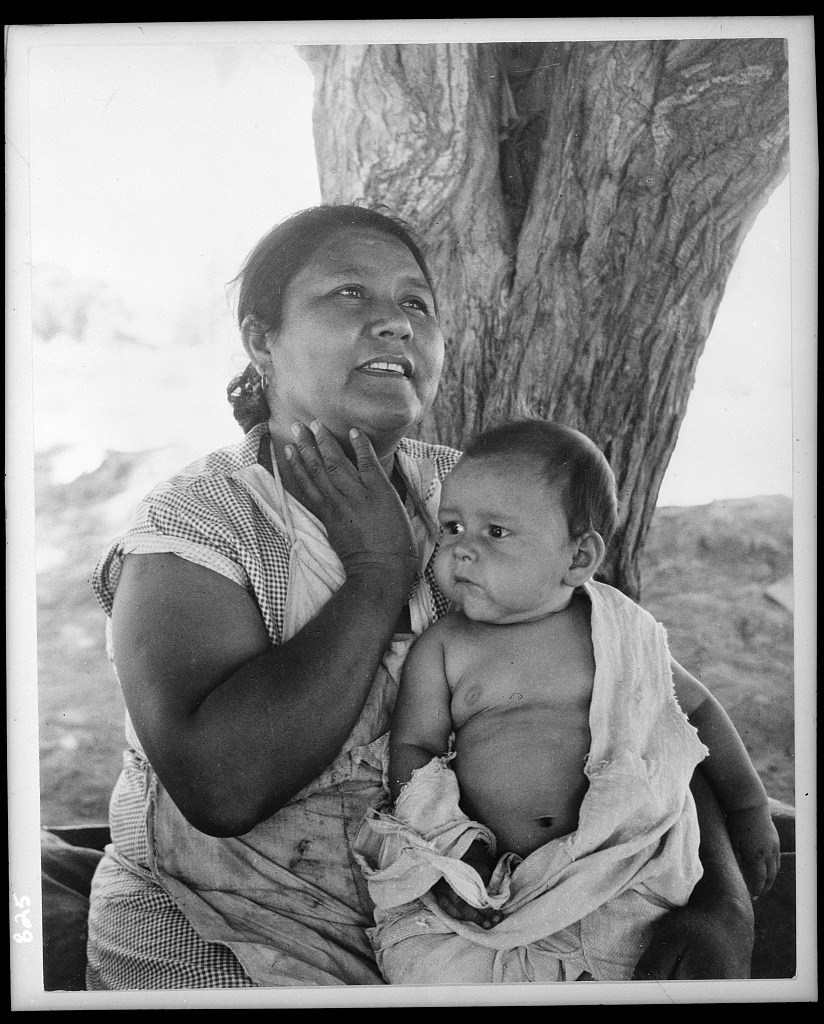

Image Caption: Mexican mother in California. “Sometimes I tell my children that I would like to go to Mexico, but they tell me ‘We don’t want to go, we belong here.'” (Note on Mexican labor situation in repatriation). By Dorothea Lange, 1935. Image from Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Finding the appropriate language to describe what happened is only part of the story. Despite the massive impact, and the illegal deportation of U.S. citizens, very few people in the U.S. know this story and even fewer learn about it in school. The Latino USA story below explores both the history and the actions taken by LA area students to make sure this history is taught in schools.

Reflection Questions

Before exploring specific issues raised by the film, begin analysis of the film with the see-feel-think-wonder thinking routine.

-

-

-

- How do you explain why newspapers and officials failed to make a distinction between Mexicans living in the U.S. and Mexican American citizens?

- Language matters. Balderrama explains that “repatriation carries connotations that it’s voluntary, that people are making their own decision without pressure to return to the country of their nationality.” He then describes the circumstances Mexicans were forced to confront. What word would you use to describe the events he described? To what extent were choices to relocate to Mexico made voluntarily? Were they choices? Who held the power, Mexicans and Mexican Americans or the U.S. or local officials?

- What distinction is Erika Lee making between “a xenophobic campaign to get rid of foreigners” and the events between 1929-1935? Why does it matter?

- The 14th amendment of the United States Constitution reads,All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.Based on the descriptions in the film and the text above, was the expulsion of Mexican American citizens, 60% of those who were relocated to Mexico, a violation of the 14th Amendment? How would you explain your answer?

- How would you describe the consequences of these deportations? Did they achieve the goals of those that argued for the exclusion of Mexicans? What price was paid by Mexicans, Mexican Americans, and the communities in which they lived?

- What would justice look like for victims of these unlawful “repatriations” and their descendants look like today? What should happen? Who might need to be involved?

- Students in the Latino USA story want this history taught. What arguments do they make? What arguments might you make about the significance of this story? Consider using the Project Zero “Three Why’s Thinking Routine.” Why does this matter to me? Why does this matter to my community? Why does this matter to the world?

- For an in-depth interview with Historian Francisco Balderrama about the expulsions, listen to his interview with NPR’s Terry Gross

-

-