Notre Dame Versus the Ku Klux Klan

Many Hoosiers actively, adamantly, and even violently opposed the Klan. Cities passed anti-mask ordinances to prevent the Klan from marching in their hoods and robes. Prominent citizens founded civic clubs “to fight the Ku Klux Klan.” The Indianapolis Times launched a multi-year “crusade” against the Klan, exposing members’ identities and combating the secret organization’s influence on Indiana politics. Black voters risked being jailed as “floaters” (someone whose vote was illegally purchased) when they came out in record numbers to cast their votes in opposition to Klan-backed candidates.

Local Catholic organizations called on politicians to denounce the Klan and include a plank in their official party platforms rejecting “secret political organizations” and supporting “racial and religious liberty.” Indiana attorney Patrick H. O’Donnell led the American Unity League, a powerful Chicago-based Catholic organization that also published the names and addresses of Klan members in its publication Tolerance. O’Donnell wrote:

We’re out to lick the Ku Klux and forever disperse them. We shall not resort to force, and all our actions will be far more open and above board than that of Klan followers who have not the courage to parade openly. Our main point of attack will be along political lines. We intend proving that the Klan seeks to foment hate and suppress those inalienable rights guaranteed by the constitution.

And while most resistance was nonviolent, not all of it was.

South Bend, Indiana, in Saint Joseph County had a large immigrant population of mainly Irish, Polish, and Hungarian origin. It was also home to the University of Notre Dame, a prestigious Catholic school that included a large number of students of Irish heritage or birth. Notre Dame historian Robert E. Burns explained that to the Klan, South Bend was their “biggest unsolved problem.”

Klan leader D.C. Stephenson hoped that a large rally in the city, the heart of Indiana Catholicism, would demonstrate the Klan’s power and dominance. If he could bait a reaction from Notre Dame’s Catholic students and South Bend’s Catholic residents, he could paint them as violent, lawless, un-American immigrants in contrast to his peaceably assembled “100% American” Klansmen. This might convince Hoosiers to vote for Klan members or Klan-friendly candidates. On May 17, 1924, just three days before the Indiana Republican Convention, the Ku Klux Klan would hold a mass meeting for its Indiana, Michigan, and Illinois members in South Bend.

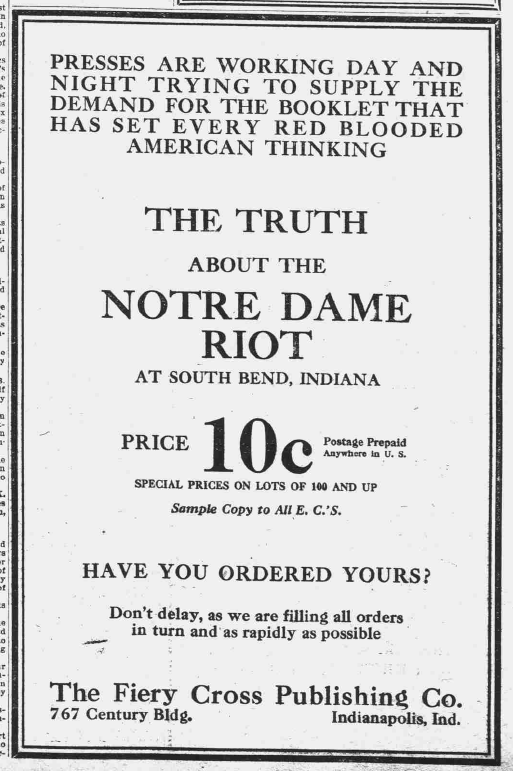

A Headline from the Ku Klux Klan Newspaper The Fiery Cross announcing a rally in heavily immigrant and Catholic South Bend, IN.

Fearful for the safety of their students and local residents, Notre Dame and South Bend officials worked to stop a potentially violent incident. South Bend Mayor Eli Seebirt refused to grant the Klan a parade permit, although he could not stop their peaceful assembly on public grounds. President Walsh issued a bulletin imploring students to stay on campus and ignore the Klan activities in town. He wrote:

Similar attempts of the Klan to flaunt its strength have resulted in riotous situations, sometimes in the loss of life. However aggravating the appearance of the Klan may be, remember that lawlessness begets lawlessness. Young blood and thoughtlessness may consider it a duty to show what a real American thinks of the Klan. There is only one duty that presents itself to Notre Dame men, under the circumstances, and that is to ignore whatever demonstration may take place today.

Father Walsh was right. “Young blood” could not abide the humiliation of this anti-Catholic hate group taking over the town. The Fiery Cross had hurled insults and false accusations at the students. The propaganda newspaper called them “hoodlums,” claimed that Notre Dame produced “nothing of value,” and blamed students for crime in the area. [39] As Klan members began arriving in the city on May 17, 1924, South Bend was ready to oppose them. The South Bend Tribune reported:

Trouble started early in the day when klansmen in full regalia of hoods, masks and robes appeared on street corners in the business section, ostensibly to direct their brethren to the meeting ground, Island park, and giving South Bend its first glimpse of klansmen in uniform.

Not long after Klan members began arriving, “automobiles crowded with young men, many of whom are said to have been Notre Dame students” surrounded the masked intruders. The anti-Klan South Bend residents and students tore off several masks and robes, exposing the identities of “kluxers” who wished to spread their hate anonymously. The Tribune reported that some Klan members were “roughly handled.” The newspaper also reported that the anti-Klan force showed evidence of organization. They formed a “flying column” that moved in unison “from corner to corner, wherever a white robe appeared.” By 11:30 a.m. students and residents of South Bend had purged the business district of any sign of the Klan.

Meanwhile, Klan leaders continued to lobby city officials for permission to parade, hold meetings in their downtown headquarters, and assemble en masse at Island Park. Just after noon, the group determined to protect South Bend turned their attention to Klan headquarters. This home base was the third floor of a building identifiable by the “fiery cross” made of red light bulbs. The students and South Bend residents surrounded the building and stopped cars of arriving Klansmen. Again, the Tribune reported that some were “roughly handled.” The anti-Klan crowd focused on removing the glowing red symbol of hate. Several young men “hurled potatoes” at the building, breaking several windows and smashing the light bulbs on the electric cross. The young men then stormed up the stairs to the Klan den and were stopped by minister and Klan leader Reverend J.H. Horton with a revolver.

The students attempted to convince Klan members to agree not to parade in masks or with weapons. While convincing all parties to ditch the costumes wasn’t easy, they did eventually negotiate a truce. By 3:30 p.m., “five hundred students and others unsympathetic with the klan” had left the headquarters and rallied at a local pool hall. Here, a student leader spoke to the crowd and urged them to remain peaceful but on vigilant standby in case they were needed by the local police to break up the parade. After all, despite Klan threats, the city never issued a parade license. The plan was to reconvene at 6:30 p.m. at a bridge, preventing the Klan members from entering the parade grounds. In the end, no parade was held. Stephenson blamed the heavy rain for the cancellation in order to save face with his followers, but the actual reason was more sinister.

Stephenson knew that he had been handed the ideal fuel for his propaganda machine. Using a combination of half truths and blatant lies, he could present an image of Notre Dame students as a “reckless, fight-loving gang of hoodlums.” The story that Stephenson crafted for the press was one where law-abiding Protestant citizens were denied their constitutional right to peacefully assemble and were then violently attacked by gangs of Catholic students and immigrant hooligans working together. They claimed that the students ripped up American flags and attacked women and children. The story picked up traction and was widely reported in various forms. In the eyes of many outsiders, Notre Dame’s reputation was tarnished. Unfortunately, they would have to survive one more run-in with the Klan before they could begin to repair it.

A booklet produced by the Klan promoting their anti-Catholic version of the events at Notre Dame

The press they garnered from the clash in South Bend had been just what Stephenson ordered. He figured one more incident, just before the opening of the Indiana Republican Convention, would convince stakeholders of the importance of electing Klan candidates in the face of this Catholic “threat.” Local Klan leaders just wanted revenge for the embarrassing episode. Only two days later, on Monday, May 19, the Klan set a trap for Notre Dame students. Around 7:00 p.m. the lighted cross at Klan headquarters was turned back on and students began hearing rumors of an amassing of Klan members in downtown South Bend. The South Bend Tribune reported, “Approximately 500 persons, said to have been mostly Notre Dame students, opposed to the klan . . . started a march south toward the klan headquarters.” Meanwhile, Klan members armed with clubs and stones spread out and waited. When the students arrived just after 9:00 p.m., the Klan ambushed them. The police tried to break up the scene, but added to the violence. By the time university leadership arrived around 10:00 p.m., they met several protesters with minor injuries. The students were regrouping and planning their next move; more violence seemed imminent. Climbing on top of a Civil War monument, and speaking over the din, Father Walsh somehow convinced the Notre Dame men to return to campus. The only major injury sustained was to the university’s reputation.

University President Father John O’Hara devised a strategy for countering the negative press coverage inflicted on Notre Dame by highlighting one university program that was beyond reproach, not to mention already popular and exciting enough to draw press coverage. Father O’Hara’s inspired strategy was to put the full weight of the university behind championing its successful football team and the respectable, upright, and modest team members. The Fighting Irish football team had finished the 1923 season with only the one loss to Nebraska and a decent amount of newspaper coverage. [50] Much more was riding on the 1924 football team’s success. The school administration, the student body, alumni, as well as Catholics and immigrants in Indiana and beyond, looked to the Notre Dame players to show the world that they, and people who shared their religion and heritage, were proud, hardworking, dignified, and patriotic. The model team could prove the Klan’s stereotypes about Catholics and immigrants had no resemblance to reality.

Father O’Hara would later become President of Notre Dame and was named a Cardinal in 1958 by Pope John XXIII.

Father O’Hara recognized that linking the players’ Catholicism with their success on the gridiron created a strong positive identity for the university. Since at least 1921, he had arranged for press to cover the players, Catholic and non-Catholic together, attending mass before away games and even on the train. He provided medals of saints for the team to wear during games and distributed his Religious Bulletin, in which he wrote about “the religious component in Notre Dame’s football success,” to alumni, colleagues, and the press. [52] According to Notre Dame football historian Murray Sperber, Father O’Hara conceived of an ambitious outreach plan for the 1924 season as a direct response to the Klan’s propaganda. In fact, O’Hara may have gotten the idea from a 1923 New York Times editorial that sarcastically reported on the reason for the Klan’s rise and extreme anti-Catholicism in Indiana:

There is in Indiana a militant Catholic organization, composed of men specially chosen for strength, courage and resourcefulness. These devoted warriors lead a life of almost monastic asceticism, under stern military discipline. They are constantly engaged in secret drills. They make long cross-country raiding expeditions. They have shown their prowess on many battlefields. Worst of all, they lately fought, and decisively defeated, a detachment of the United States Army. Yet we have not heard of the Indiana Klansmen rising up to exterminate the Notre Dame football team.

This editorial, and other similar articles, implied that making the football team the symbol of Catholicism at Notre Dame could serve to combat the Klan in the press. In 1924, Father O’Hara created a series of press events to align with the game schedule, hoping to link the school’s proud Catholicism with the excitement of the winning team. Of course, for this strategy to work, the team had to keep winning games.

Coach Knute Rockne, who had led the Fighting Irish since 1918, had built an almost unstoppable football team by the close of the 1923 season. In six seasons, the team only lost four games. Two of these were tough losses to Nebraska where the players faced anti-Catholic hostilities. In 1924, with the eyes of the nation on them, the Notre Dame team needed a perfect season. Luckily “the 1924 Notre Dame Machine was bigger and better than ever,” according to the editors of the Official 1924 Football Review.

As the Fighting Irish won game after game in the fall of 1924, Notre Dame alumni on the East Coast began drumming up publicity in anticipation of an important game against the Army team in New York City. The graduates fed Notre Dame-produced press statements to New York newspapers and proselytized at Catholic social organizations like the Marquette Club. Coach Rockne even hired a New York Times writer for an exorbitant sum. This all but guaranteed a round of good press for the Irish. All they had to do was win.

The Irish beat Army on October 18, 1924 in front of 60,000 people due in large part to their legendary backfield. Writing for the New York Herald Tribune, reporter Grantland Rice went further in praising the backfield of Harry Stuhldreher, Don Miller, Jim Crowley, and Elmer Layden. In a passage described by Sperber as perhaps the most famous in sports history, Grantland wrote:

Outlined against a blue, gray October sky, the Four Horsemen rode again. In dramatic lore, they are known as Famine, Pestilence, Destruction and Death. These are only aliases. Their real names are Stuhldreher, Miller, Crowley, and Layden.

In fact, this famous line came from Notre Dame’s own publicity machine. George Strickler, a press assistant employed by the university had just seen Rex Ingram’s new movie, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Strickler mused that the Notre Dame backfield recalled “those ethereal figures charging through the clouds.” Rice took the idea and made it his lead. The article quickly found a life of its own. The catchy lead was picked up by other newspapers and the nickname stuck. Strickler was delighted with the press coverage and determined to make the most of it. He called the university and arranged to have a photographer shoot a picture of the “horsemen” upon their return — on horseback, of course.

The Four Horsemen of Notre Dame

The publicity continued to build as Notre Dame defeated team after team, including their rival Princeton and Big Ten teams. Meanwhile, the Klan had not forgotten about South Bend. On November 8, while the Fighting Irish celebrated their win over Wisconsin, 1,800 Klansmen and women “from Chicago and from a number of Indiana cities,” gathered just outside the city limits. Between six and seven o’clock they paraded through the streets of South Bend, a quick clip compared to other Klan parades and events. There was little reaction to their presence and the South Bend Tribune reported that “few people were on the streets.” It’s not clear why there was no response from students. Perhaps they simply didn’t have advance notice of the parade, and when the event happened quickly, they didn’t have time to form a response. Maybe they simply refused to be baited into further confrontations. Either way, the Klan had surely succeeded in reminding the Irish Catholic students that the threat of violence still loomed.

The Irish also continued to face prejudice on the field. They were determined to beat the Nebraska Cornhuskers, the team that had hurled racist epitaphs at them the previous season. The November 15 game was held at home in South Bend. Notre Dame supporters packed the stands at the recently enlarged Cartier Field while overflow fans stood on the sidelines or even sat on the fences. The local newspaper estimated the crowd at 26,000 people, the largest to date. Recognizing the increasing popularity of the Notre Dame team to those in the wider area, the WGN radio station in Chicago delivered a live broadcast of the game. Likewise, the South Shore interurban line, which ran between South Bend and Chicago, created large color posters of Notre Dame football players in action to advertise their service.

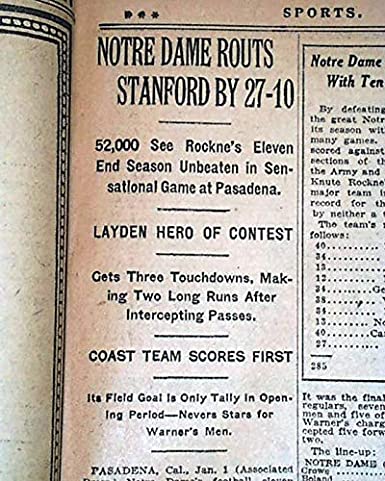

The Irish thoroughly outplayed the Cornhuskers with much of the credit going to the Four Horsemen. Notre Dame beat Nebraska 34-6, but even that score did not reflect how well the Irish played. The Tribune reported, “Twenty-three first downs for Notre Dame gave the fans some idea of the complete swamping the western players received.” The win was important for two reasons. First, the symbolic victory of the hardworking and stoic Irish Catholic school over a team with anti-Catholic fans was significant to their Irish Catholic supporters in an era dominated by the Klan. Second, making 1924 an undefeated perfect season would give them the public platform they needed to further improve the reputation of Notre Dame. They went on to beat their last two opponents for a perfect season and at the start of 1925, defeated Stanford to win the Rose Bowl.

More significantly, the several week tour by rail of the Midwest and West around the Rose Bowl Game that was masterminded by Father O’Hara forever repaired the university’s reputation. According to Notre Dame historian Robert E. Burns:

O’Hara saw the Rose Bowl invitation as an almost providential opportunity to counter the extremely negative Klan-inspired image of Notre Dame . . . [and] might well turn out to be the most successful advertising campaign for the spiritual ideals and practices of American Catholicism yet undertaken in this century.

The Klan continued to fume over the May 1924 clash at South Bend in the pages of the Fiery Cross, but were unable to gain a foothold in the city. In other areas of Indiana, however, the Klan dominated – and influenced policy at the state and national level.

Resources and Further Reading

For the full story of the University of Notre Dame’s opposition to the Indiana Ku Klux Klan, including sources and notes for this essay, see the blog series “Integrity on the Gridiron” by Jill Weiss Simins for the Indiana History Blog:

Part One: Opposition to the Klan at Notre Dame

Part Two: Notre Dame’s 1924 Football Team Battles Klan Propaganda

Part Three: The Notre Dame Publicity Campaign That Crushed the Klan

For a thorough examination of the opposition to the Klan by African Americans, Jews, Catholics, lawyers, politicians, labor unions, newspapermen and more see: James H. Madison, “The Klan’s Enemies Step Up, Slowly,” Indiana Magazine of History 116, no. 2 (June 2020): 93-120, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/indimagahist.116.2.01