The Mother-Tongue: Bilingual Education Then and Now

By Natasha Karunaratne

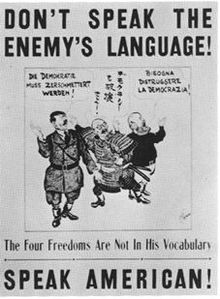

A poster of WWII era discouraging the use of Italian, German, and Japanese.

While it may seem like the education of immigrant children is newly controversial, the question of how to educate immigrant children has been an ongoing debate within the United States. At stake is the question about the best way to integrate newcomers to be a part of their new homeland? What do they need to know to be successful? How should they be taught the values, culture, and customs of their new country? One area where these arguments have focused is on language. Should schools allow newcomers to use their native languages as part of their education? Should schools offer bilingual classes to engage and educate students? The fight over bilingual education in the U.S. was brought before the U.S. Supreme Court as early as 1923, in the case of Meyer v. Nebraska. Lutheran school teacher Robert T. Meyer was arrested from the Zion Parochial School in Hampton, Nebraska, for conducting religious education in German during recess to his class of German immigrant children. On this particular day, Meyer was teaching his classroom about the story of Moses when the county attorney walked in the classroom. Meyer was tried and convicted for violating the Siman Act, which was passed in Nebraska in 1919 to prohibit private, denominational, parochial and public schools from teaching in any language other than English. However, the Supreme Court ruled that the law violated the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Below we have presented the arguments stated by each side of the case, as a way to engage students in this important discussion.

Petitioner: Meyer

When asked why he continued to teach in German even in the county attorney’s presence, Meyer said that “I knew that, if I changed into the English language, he would say nothing. If I went on in German, he would come in, and arrest me. I told myself that I must not flinch. And I did not flinch. I went on in German.” Why? “It was my duty. I am not a pastor in my church. I am a teacher, but I have the same duty to uphold my religion. Teaching the children the religion of their fathers in the language of their fathers is part of that religion.” In Meyer’s eyes, teaching the children in German ensured that they would grasp the words of his religious teachings, which was the goal of his job as not only a pastor, but as a teacher.

Respondent: State of Nebraska

According the the court records, the state of Nebraska claimed that “to allow the children of foreigners, who had emigrated here, to be taught from early childhood the language of the country of their parents was to rear them with that language as their mother tongue. It was to educate them so that they must always think in that language, and, as a consequence, naturally inculcate in them the ideas and sentiments foreign to the best interests of this country.” In this statement, the state argued that teaching immigrant children in their mother tongue from an early age would slow down their learning of English, and thereby their assimilation to America. Therefore, the law called for foreign languages to only be taught after 8th grade, to ensure that immigrant children could learn their mother tongue, but with having English as their first language. According to the Encyclopedia of Bilingual Education, a Nebraska congressman is said to have debated that “if these people are Americans, let them speak our language. If they don’t know it, let them learn it. If they don’t like it, let them move.”

The Judicial Ruling:

The Supreme Court ruled that the state of Nebraska violated Meyer’s rights, making this case the first national law to tackle bilingualism and the education of migrant children. While the Siman Act had been passed in the state of Nebraska, Nebraska was far from alone in passing such a law – as by the early 1920s, in the peak of anti-German sentiment in America, 34 states had passed English-only requirements in their schools. Such laws were said to target “Catholic and Lutheran schools that taught religious subjects in the family language of immigrant children, rather than in English,” as these different languages and cultures were seen as dangerous and “un-American.”

Forty four years after Meyer v. Nebraska, federal support for bilingual education was recognized under the Bilingual Education Act of 1968, which did not force school districts to offer bilingual programs, but rather encouraged them to experiment with new pedagogical approaches by funding programs that targeted principally low-income and non-English speaking populations. According to David Nieto’s A Brief History of Bilingual Education in the United States, this law because known as the “most important law in recognizing linguistic minority rights in the history of the United States.” However, in the eighties, the Reagan administration led a major campaign against bilingual education, under a “back to basics” education platform. According to James Crawford’s Bilingual Education: History, Politics, Theory, and Practice, the Reagan administration defined the United States as a “nation at risk of balkanization” and blamed non-English speaking communities for such a risk, leading Senator Hayakawa of California to introduce a constitutional amendment aimed at adopting English as the official language of the United States, although it inevitably didn’t pass. In 1994, the Bilingual Education Act was reauthorized for the purpose of “developing bilingual skills and multicultural understanding.” However, in 2002, anti-bilingual sentiments found support under George W. Bush’s No Child Left Behind Act. According to Nieto’s A Brief History of Bilingual Education in the United States, the policy “imposed a high-stakes testing system that promoted the adoption and implementation of English-only instruction” which still has lasting implications today on bilingual education today. While numerous states have gone on to pass laws both expanding and restricting the use of bilingual education since Meyer v. Nebraska, the case maintains a legacy of establishing the United States as an English-speaking country for children of all mother-tongues.

Reflection Questions:

- What was the main motivation for passing Meyer v. Nebraska? What was the historical context in which this debate around bilingual education arose? Who was the target of this law?

- Why do you think many people see bilingual education as a threat? How may these motivations for bilingual or anti-bilingual education have changed over the 1900s?

- What was Meyer’s reasoning for continuing to teach in German even while knowing it was illegal?

- What was the state of Nebraska’s reasoning for outlawing bilingual education prior to 8th grade?

- In your opinion or the opinion of others, what within our current American education system is often considered to be “un-American” today?